Undertaking the Hajj is really and truly making a journey to the heart of Islam, to the Ka‘ba, ‘the first house’ set up for the worship of the One God, the heart of the Islamic faith.1 The pilgrimage to the Ka‘ba in Mecca is the fifth pillar of Islam, after the declaration of faith (shahada), ritual prayer (salat), obligatory alms (zakat) and the fast (sawm) of Ramadan. Although it comes fifth, it is very special in its impact. Prayer is familiar to Muslims every day, but the Hajj is required only once in a lifetime. It also involves an unforgettable journey which adds to its mystique and appeal. No one acquires a title for praying or fasting, but you do after taking that journey to the heart of Islam. The Hajj rites are, moreover, an obligation on all Muslims, attested by the Qur’an, the supreme authority in Islam; the Hadith (traditions of the Prophet), the second authority; the consensus of Muslim scholars, and the continued practice ever since the time of the Prophet Muhammad.

From its institution as a pillar of Islam, the word ‘Hajj’ has applied only to the pilgrimage to Mecca; no pilgrimage to any other place is called Hajj. The Hajj rites are fixed and have been handed down through the ages, and all Muslim pilgrims must fulfil the required acts. In this way the Hajj connects Muslims historically through the generations, as well as geographically to other Muslims around the world at any particular time. It is one of the most important unifying elements in the Muslim community (umma), and it is a journey that marks a huge change in the spiritual and social life of the pilgrims.

The origin of Hajj

The origin of Hajj

According to the Qur’an, the Hajj did not start with the Prophet Muhammad but thousands of years before, with the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham), the supreme example in the Qur’an of dedication to the One God and submission (islam) to His will.2 Most of the Hajj rituals are actually based on the actions of Ibrahim and his family, as stated in the Qur’an: God says in the Qur’an: ‘We showed Ibrahim the site of the House’ (Q.22:26), relating how Ibrahim and Isma‘il (Ishmael) built up the foundations of the Ka‘ba and the beautiful prayers they recited, and how God commanded Ibrahim: When these verses are heard or recited by Muslims, when

They repeat the prayers of Ibrahim, with their sentiments, their words and the rhythm they have in Arabic, it moves them to tears and deepens their longing to respond to that call made thousands of years ago and undertake the journey.

Performing the Hajj

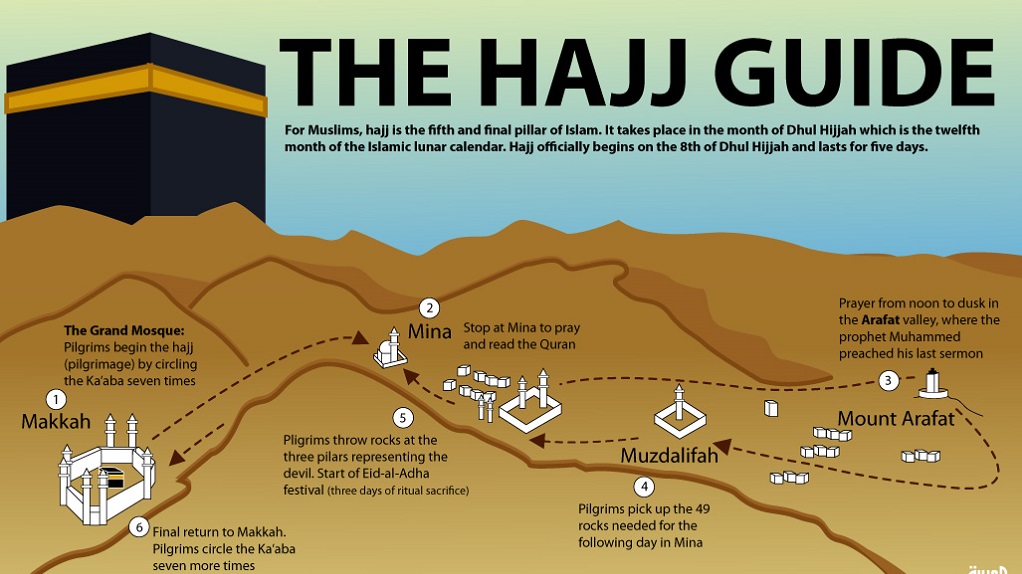

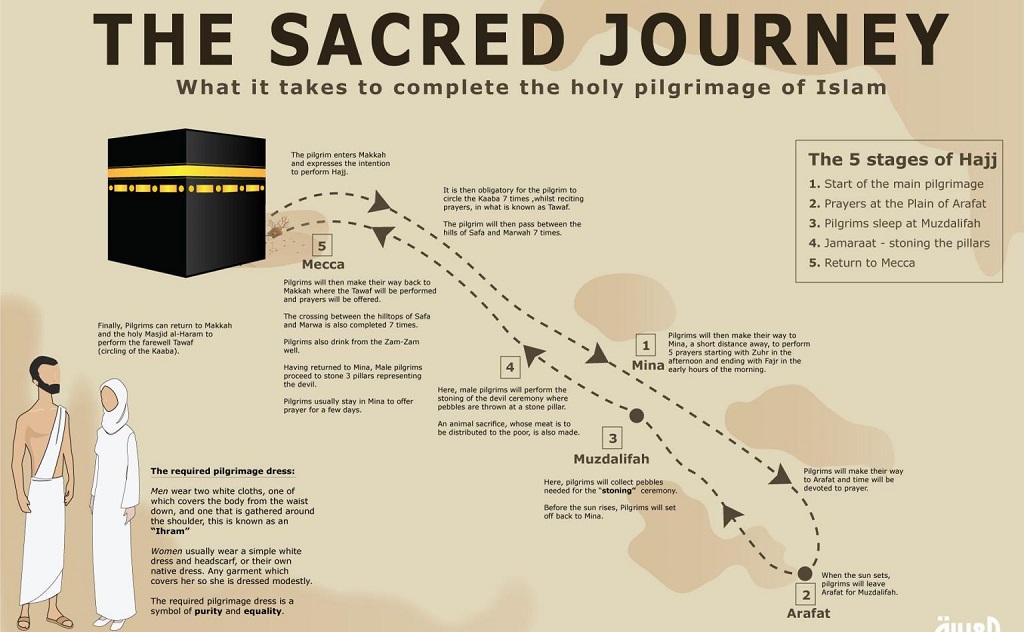

The Qur’an states that Hajj should take place ‘in the specified months’.4 These are the last three months of the Muslim calendar and this period is known as miqat zamani (fixed time). In the past, pilgrims would start their journey to Mecca early within this period, but the main acts of the Hajj itself take place in five days during the third (and last) of these months, 8th–13th Dhu al-Hijja. Hajj rituals start with consecration (ihram) for Hajj, which must be made by the time pilgrims reach the specified fixed places, each known as miqat makani (the fixed place), on the roads to Mecca from the various directions. The closest miqat to Mecca (Yalamlam) is the one on the road from the Yemen, 50km (31 miles) away. The furthest one (Dhu al-Hulayfa) is only a few kilometres from Medina, which is over 300km (185 miles) from Mecca.5 In the days before modern transport this meant lengthening the period of consecration to include this arduous journey, but also to provide further spiritual feelings and blessings.

When pilgrims enter into ihram, it is recommended that they have a full body wash and perfume themselves, and men must change into the ihram clothing, consisting of two pieces of seamless white cloth (such as towels), one fixed round the waist and the other covering the top of the body.These can be secured with pins or a belt. Footwear should also be simple and not sewn. Women’s clothing for Hajj is normal and can be of any colour, although usually they choose white, but they should not cover their faces. Once the pilgrims are in ihram they must not use perfume, shave, cut their hair or nails, or have sexual intercourse. Entering into ihram is a high spiritual moment, one the pilgrims have long anticipated. They leave behind any luxury living, any social distinction and dedicate themselves to worship. They begin the talbiya, chanting in Arabic ‘Labbayk allahumma labbayk’, ‘Here I am, Lord, responding to Your call [to perform the Hajj]. Praise belongs to You, all good things come from You and sovereignty is yours alone.’ This is constantly repeated during the Hajj, especially when meeting other pilgrims, moving from place to place, and after the daily prayers. The pilgrims are unified by chanting in the same language and also by their simple clothing, worn by people of every status, colour, language and background.

It is interesting to note here that although the Hajj ritual takes only five days, within a 25km distance from Mecca, the consecration and consequent sense of security and peace spread much further afield in time and place.

Ibrahim prayed that God would make Mecca peaceful and secure. Pilgrims must not hunt, kill animals or cut any plant Throughout the Hajj period and during the various rituals, there are special du‘a prayers for pilgrims to say, many of which were spoken and recommended by the Prophet Muhammad. There are handbooks of these prayers, written in Arabic, and also transliterated with translations for non-Arabs. Pilgrims prefer to recite them in Arabic, in the words uttered by the Prophet himself, and consider them more effective than any other prayer in any language. Each group, large or small, normally has a guide (mutawwaf ) who chants, and they repeat the prayers after him, interspersed with the talbiya.

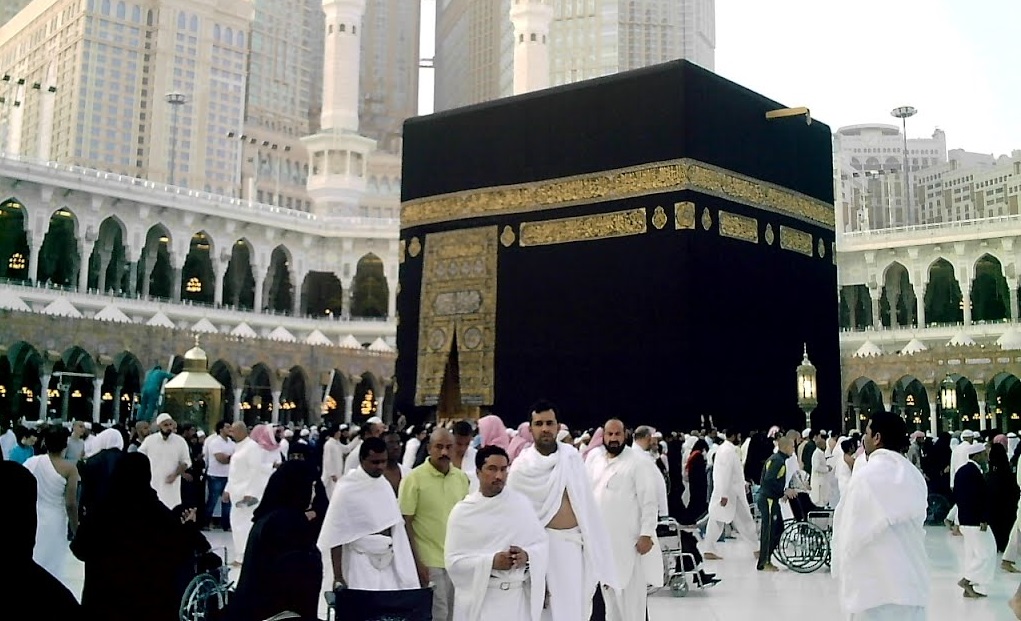

All this intensifies the spirituality of the Hajj season and enhances the unity of the pilgrims. When pilgrims arrive in Mecca they make their first visit to the Haram, the sacred precinct, with its grand mosque. The first glimpse of the minarets and mosque is an unforgettable experience shared with huge numbers of people from all over the world, most of whom are seeing it in person for the first time. It is recommended that as they go in through the Gate of Peace (Bab al-Salam) they recite in Arabic,9 ‘Lord, open the gates of Your mercy for me. You are peace, from You comes peace, give us Your greeting of peace and admit us to Paradise, the land of peace. Glory be to You, Lord of Majesty and Honouring.’ On entering the mosque, it is the Ka‘ba that attracts the pilgrims’ eyes. There they will glorify Allah and repeat: There is no god but Allah, alone with no partner. Dominion and praise belong to Him, and He has power over all things. Peace be upon our Prophet Muhammad and on his family and companions. Lord, increase this House in honour, glory, reverence and respect and increase those who glorify it and visit it, make pilgrimage to it and increase their respect and goodness.10 Pilgrims approach the Ka‘ba, happy to be at the actual building that Muslims face in their daily prayers all their lives and after death when they are buried. They go as near as possible to the Ka‘ba and do the tawaf (circumambulation) seven times, anti-clockwise, starting from the eastern corner in which the Black Stone is embedded, thus re-enacting the actions of the Prophets Ibrahim, Isma‘il and Muhammad and all succeeding generations of Muslims. Every time they pass the Black Stone, if possible they should kiss, touch or at least point to it, saying ‘Allahu akbar’, ‘God is greater’. While walking round the Ka‘ba, pilgrims continually recite prayers as mentioned above, particularly: ‘Lord, give us good in this life and good in the hereafter and protect us from the torment of the Fire’.

Those near the Ka‘ba often lay their hands on the wall or reach for the velvet cover, praying most earnestly for the heartfelt needs of themselves, members of their families and the many who have asked the pilgrims to pray for them. Later at home, when someone wants to ask the hajji earnestly for something, they may say, ‘I beg you by the Ka‘ba on which you placed your hand’. The pilgrims do the tawaf together, men, women and children from all nations. The infirm are carried on litters by strong men. This ritual continues night and day and a considerable number do it as many times as they can. Following this it is recommended to do two rak‘as (prayer cycles) at the Maqam Ibrahim (the place where Ibrahim – peace to all. They must also refrain from indecent speech, misbehaviour and quarrelling,7 jostling or rushing: all very fitting, considering the huge crowds in the limited spaces. The Prophet emphasized that those who performed the Hajj without committing these forbidden acts would return home as free from sin as on the day their mother gave birth to them.8 These restrictions apply not only when the pilgrim is in Mecca and its surroundings but also in the entire area between the miqat makani and Mecca. Such is the effect of the Hajj in establishing peace and good behaviour in that land.